The winter skies of 1883 are immortalized in a series of vivid pastels by the painter William Ascroft, and a poem by then-poet laureate Alfred Tennyson. Their inspiration: the extraordinarily colorful sunsets that they and people across the world observed. The cause of those sunsets: the stratospheric cloud of dust from the 20-cubic kilometers of rock emitted when Mount Krakatau in Indonesia erupted on 26th August 1883 (this was 20 times that of the Mount Saint Helens eruption of 1980). The climactic eruption of Krakatau was so massive that people in both India and Australia could hear it 4,600 kilometers away. It generated a series of massive tsunamis—some reaching as high as 40 meters—that accounted for 90 percent of the official death toll from the eruption, which, according to the Dutch authorities at the time, was 36,417 people. A four-year volcanic winter followed the explosion with unusually cold temperatures and record snowfalls worldwide.

Local islands and the Ujung Kulon peninsula were devastated by a series of tsunamis from the eruption with entire villages wiped out in an instant. The Ujung Kulon peninsula, only 55 kilometers across the sea from Krakatau, was blanketed in a layer of ash 30 centimeters deep, and people never returned. Free from human disturbance and with suitable conditions for ecological recovery, the native fauna and flora recovered on the peninsula. The government of Indonesia established the area as a nature reserve in 1921, and upgraded it to a game reserve in 1958, a nature reserve in 1967, and a national park in 1992. Today it holds the largest remaining area of lowland forest on the Java plain and has been declared both a World and Asian heritage site.

Born out of the ashes of volcanic catastrophe, Ujung Kulon National Park now supports the world’s only population of Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus). The site’s inherent vulnerabilities however, including to volcanic eruption and tsunami, mean the species remains just seconds away from potential extinction.

My introduction to Javan rhino conservation came in 2005 when I was asked to advise on the Javan rhino project in Cat Tien National Park by WWF Vietnam, who I worked for at the time. I attended a workshop to plan future conservation efforts and was surprised that no decisions could be made because the lack of clarity on the number of rhinos. If there were too few, should they be left to go extinct, or caught for conservation breeding efforts? If there were more than thought, how could their habitat be extended when local communities were expanding their footprint into the rhino’s habitat? It was political gridlock. Counting the animals therefore became a higher priority than it would be otherwise. In 2007 I moved to the U.S. office of WWF and found myself in a position to help with this problem. Through fundraising and partnership building we were able to launch a comprehensive survey of the area in 2009, which led to the horrific discovery that the last rhino on mainland Asia had been poached.

Witnessing the extinction of this sub-species was horrific and about as low a point in a career as a conservationist can get. We learned many valuable lessons, however, and we boldly published our findings so the rhinos were not forgotten and the world could learn from the mistakes that had been made in Vietnam . I’m not sure if the Vietnamese rhinos could have been saved, but it definitely highlighted that species can—and do—go extinct if we don’t act in a timely manner.

Asian rhinos?!

Most people think of rhinos as African species living amongst the backdrop of grasslands or wooded savannahs. Few are aware that three of the five species of rhinoceros are found only in Asia: the Greater one-horned or Indian (Rhinoceros unicornis), the Lesser one-horned or Javan, and the Sumatran (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis). The Greater one-horned rhino is restricted to the alluvial Terai-Duar grasslands of India, Nepal and Bhutan, and conservation efforts since the 1980s have led to a range-wide recovery of the species . The Sumatran rhino is very distinct, not only because it is the only Asian species to have two horns, but in that it is more closely related to the extinct Woolly rhinos than the other four extant species of rhino. The Sumatran rhino is on the verge of extinction with fewer than 80 individuals scattered over multiple small and isolated sub-populations across Sumatra and Borneo . The Sumatran rhino was probably hunted out of the majority of its historical range, and although poaching remains an ever-present threat, the species’ rarity and the isolation of individuals means that very few animals are breeding. Without urgent consolidation of the populations to increasing breeding rates, the species will slip into extinction. For more information on the efforts to save the Sumatran rhino visit www.sumatranrhinorescue.org.

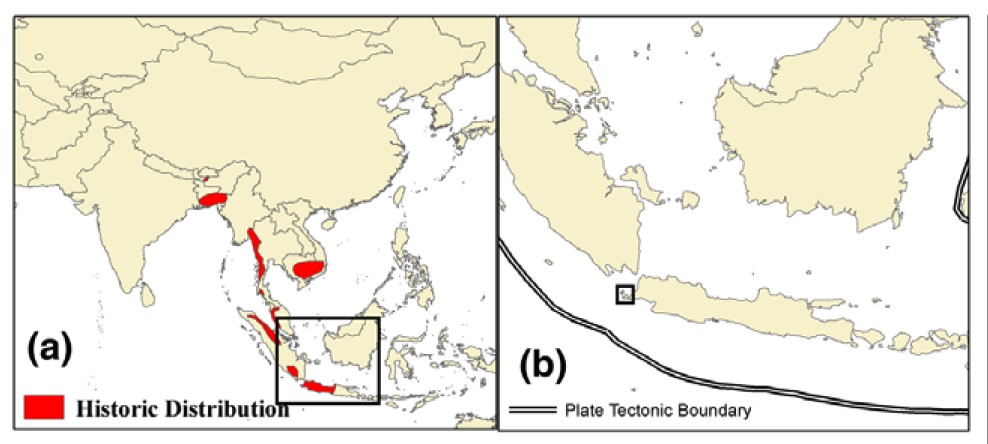

Three sub-species of Lesser one-horned or Javan rhino were known, although only one remains today. The South Asian sub-species (R.s. inermis) ranged across northeastern India, Bangladesh and Myanmar. The mainland Southeast Asian sub-species (R.s. anamiticus) was found in Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. The only remaining sub-species is the Sundaic form (R.s. sondaicus), which was found across Sumatra and Java, but is now found in a single site, Ujung Kulon National Park in west Java, Indonesia.

Recent records of Javan rhino come from just two locations: Cat Tien National Park in Vietnam, which is lowland rattan dominated semi-evergreen forest, and Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia, which is lowland evergreen and palm-dominated forest. However, these habitat types are not necessarily the preferred habitat of the species, and in fact may represent more of a quirk of history. Historical records show the species was found in the mangroves of the Sunderbans, mixed semi-evergreen forests across Indochina, and alluvial floodplains of north-east India and Bhutan. It has even been recorded roaming up into montane forests, although this is probably not its preferred habitat. The fact that the Javan rhino was lost on Sumatra whereas the Sumatran rhino survives here until the present is probably due to the Javan’s preference for lowland forest where it is more susceptible to hunters. It appears that the species however, was never found in the deciduous forests of east Java and Southeast Asia .

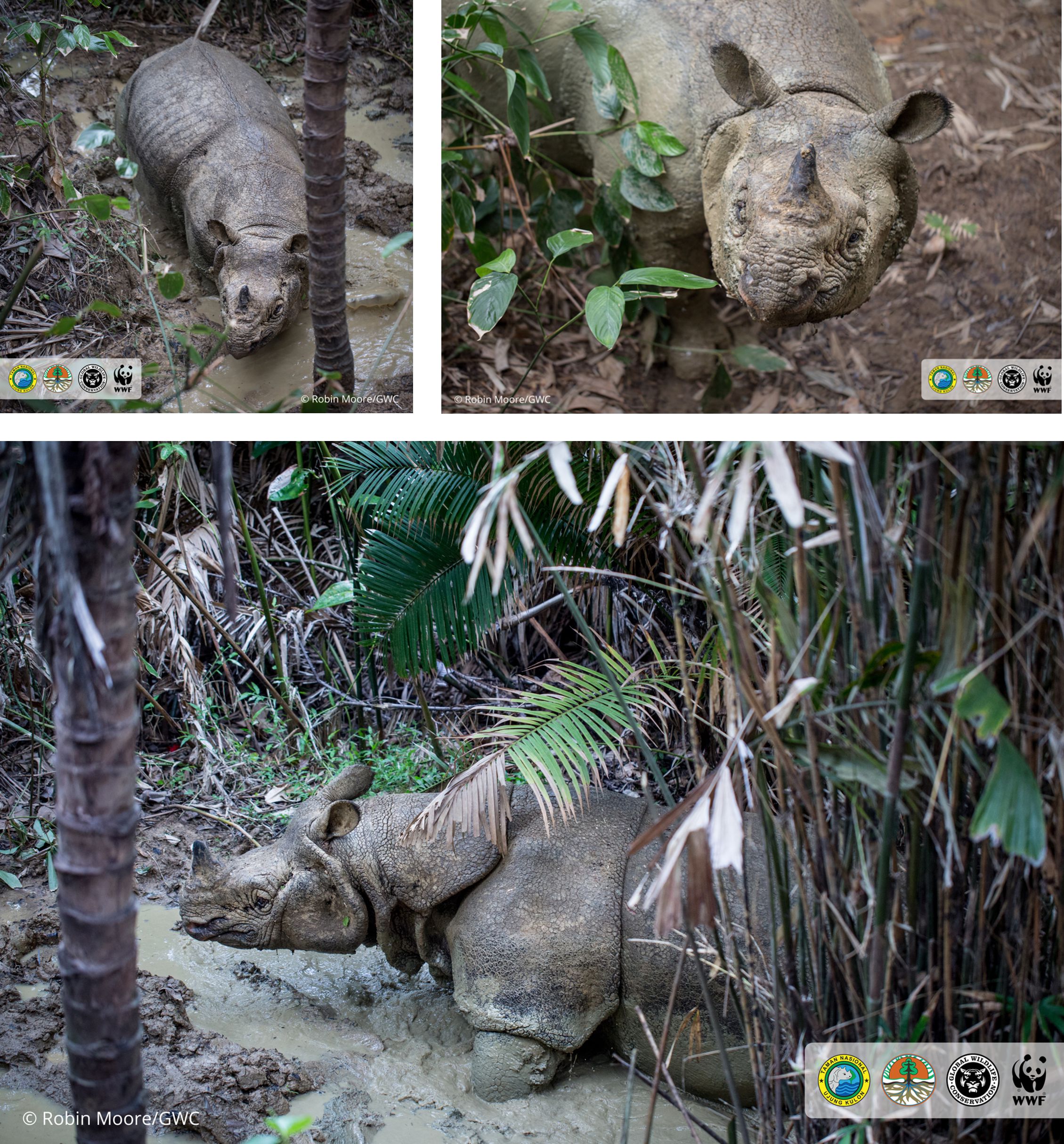

Although very little is known of its ecology, the Javan rhino appears to be primarily a generalist browser, but will graze in suitable habitat. It is smaller than the Indian rhino (305-344 centimeter head-body length, 150-170 centimeter shoulder height, and 1,200-1,500 kilograms in weight), but similar in appearance with a more extended upper lip, an independent skin shield shaped like a saddle on its nape, a tail that protrudes further from the body so is fully visible in side profile, flat epidermal polygons providing its skin a reticulated pattern, and only males have a nasal horn.

Range collapse and the start of a recovery

The Javan rhino was historically found across a large proportion of Asia from Java to northeast India. Not only was the species widely distributed, but reports from the mid-1700s suggest it was found at high densities, and was in fact a crop pest. Bounty records between 1 September 1747 and 14 January 1749—that is 501 days—showed that 526 Javan rhinos were killed in Indonesia for crop protection .

Habitat loss across Asia, which disproportionately impacts lowland forest, would have been a major contributor to the species’ decline across its range. However a combination of hunting by the colonial gentry which was often far from sustainable , poaching to supply the 2,000-year-old demand for rhino horn, and the persecution of rhinos as a crop pest is what probably led to the species’ extirpation across most parts of its former range. It appears that the species was common across its range until the mid 1800s, but after that it started to disappear. It disappeared from the Sundarbans in the late 1800s; the last animals observed in Sumatra, Malaysia and Cambodia were all in the 1930s; the last observation in Myanmar was in 1960; and reports from Thailand trickled in until the 1970s.

The species was thought to be extinct in Vietnam until reports of an animal being hunted surfaced in 1988. Initial surveys in 1989 suggested 10-15 animals may be present in the area around Cat Tien National Park, although by 1991 the only evidence came from the Cat Loc sector of Cat Tien National Park. A definitive study combined results of an intensive, systematic survey of Cat Loc between October 2009 and April 2010 with genotyping and genetic sexing of faecal samples collected during the survey, and bacterial diversity assay of 110 faecal samples collected from Cat Loc both during the survey and from previously collected faecal samples from between 2003 and 2006 Vietnam . DNA analysis from the survey showed only a single animal was present and that this matched the DNA of an animal found poached in April 2010. The bacterial diversity assay found evidence of two rhinos in the period between 2003 and 2006, but only one during the 2009-2010 survey period. We concluded that the Vietnamese rhino, and therefore the last individual of the R.s. sondaicus sub-species, had been poached to extinction.

Conservationists think that the population of Javan Rhinos in Ujung Kulon has hovered around 50-60 animals since the 1980s after recovering from an estimated 21-28 individuals in 1967. The first statistically robust survey in 2013 produced an estimate of 58-61 and annual monitoring by the park authorities since then has seen the number increase to 68 in 2017. When I started supporting work on the Ujung Kulon population in 2007 with WWF, the conservation community was not fully unified behind a single plan to save the species. The first comprehensive census of the Ujung Kulon rhino population was conducted by the entire conservation community however, with it being designed by my team in the United States, funded by an array of international partners, implemented by all local partners, and its analysis supported by international experts in statistics.

This census allowed us to plan future conservation efforts based on data for the first time . The models from this planning exercise demonstrate the need to establish a second population and how we can do so without harming the viability of the Ujung Kulon population. They also show how we can increase the population in Ujung Kulon by increasing the area’s carrying capacity. Ultimately they demonstrate how scary the situation is and how tenuous the species’ future is if poaching, disease, or a tsunami hit the population.

The cumulative efforts of the park authorities, WWF, YABI (the Indonesian Rhino Foundation), and the International Rhino Foundation to recover the Javan rhino are clearly having an impact, which is evident by the growing population in the park. But we can—and must—do more if we are to ensure a long-term, viable future for the species.

Ticking time bomb

Despite the slow, steady success of Javan rhino conservation, the species faces an array of threats—all of which are significant on their own and could lead to the rhino’s extinction—but in combination makes the survival of the Javan rhino extremely precarious. Major threats to the survival of the species include:

Poaching

The last-known rhino poaching incident in Ujung Kulon National Park occurred in the 1990s, but poaching is an ever-present threat that must never be underestimated. The last Javan rhino in Vietnam was poached in 2010. Rhino poaching in Africa increased 1,000 percent between 2007 and 2015 as demand in Vietnam and China morphed and grew dramatically, and recent seizures of Sumatran rhino horns in Indonesia demonstrate that the threat of poaching remains.

Volcanic eruption

Anak Krakatau volcano, the successor of Mount Krakatau, is active and grows larger each year and could erupt with little warning. An eruption would likely lead to forest fire, rock fall and deadly gas across the Ujung Kulon peninsula. Furthermore, an eruption is predicted to produce considerable tsunamis with wave heights of 7.9 to 21.0 meters.

Tsunami

A recent study found that a tsunami as high as 10 meters (or about 33 feet), which is projected to occur within the next 100 years, could threaten 80 percent of the area with the highest density of rhinos in Ujung Kulon .

Disease

In December 1981 and January 1982, five rhinos in Ujung Kulon died presumably as a result of disease, either Anthrax or Hemorrhagic septicemia, known locally as septicemia epizootica. The latter killed 50 buffalo and 350 goats in the park surroundings in November 1981. Between 2010 and 2012, four rhinos died of unknown causes, although veterinarians suspected Hemorrhagic septicemia as the cause for at least two of the deaths, and Hemorrhagic septicemia is commonly found in the more than 6,000 water buffalo in the villages surrounding the park. A recent study found that 90 percent of buffalo in villages adjacent to the core rhino area also have trypanosomes .

Reduced carrying capacity

Ujung Kulon National Park is 38,000 ha in size, but only a proportion of this is suitable habitat for Javan rhinos, and little suitable habitat exists around the park that would permit a sensible park expansion to provide more space for the rhinos. It is believed that between 80 and 100 rhinos could live in the park if all suitable terrain and habitat was available to them . A native palm, Arenga obtusifolia, has been spreading over the core rhino area of Ujung Kulon, shading out the understory and as a result reducing the amount of browse available to the rhinos. The palm now covers more than half of the area inhabited by rhinos. This decreased availability of food reduces the carrying capacity of the park and ultimately slows the breeding rate of the rhinos.

Small population biology

The smaller a population gets, the more likely its size alone becomes a driver of its decline. Demographic impacts (e.g. skewed sex ratios), environmental impacts (e.g. changes in browse availability), and inbreeding depression (e.g. reduction in fertility), can all drive the population to extinction through slow, yet irreversible declines.

The future

We know how to save rhinos from going extinct and how to recover their populations. The Southern white rhino population was reduced to less than 100 individuals at the turn of the 20th century, but has rebounded to more than 20,000 today. Black rhinos were reduced to 2,475 in 1993, but have recovered to more than 5,000 today. The Greater one-horned rhino population has been recovered from around 100 at the turn of the 20th century to more than 3,300 today. These recoveries were hard fought through a combination of intensive protection, habitat management, and active population management, especially translocations to increase the area inhabited by each species. Using the same principles, we can catalyze a similar recovery of the Javan rhino.

Despite the success of conservation efforts to date, in order to ensure a long-term future for the Javan rhino, we have to work simultaneously on two parallel strategies:

Firstly we need to protect and expand the population in Ujung Kulon. We have to significantly increase the surveillance and protection afforded to the population—as poaching becomes more professional, so we, too, must elevate our level of sophistication and professionalization in combatting poaching and monitoring the population. We must also protect the rhinos from disease through livestock husbandry and veterinary programs in the villages around park. We must make more of the park available to the rhinos so they can expand their population, which means controlling the Arenga palm and reducing disturbance by villagers. To enable all of this, strong support must be built among the local communities that border the park so they are more supportive of rhino conservation efforts.

Secondly, we must establish a second, and eventually a third, population of Javan rhinos so that all rhinos are not in the same basket. Our basket is threatened by poaching, disease, volcanoes, and tsunamis—it is just a matter of time before we wake up one morning and realize we were too late to establish a second population. The devastating tsunamis of 2004 and 2018 in Indonesia are stark reminders of what could befall Ujung Kulon any day. The problem is that there remains little suitable forest on Java and forest on Sumatra is under intense threat. Few places within the historical Indonesian range of the species have managed to control poaching. A few forest fragments on Java have been identified as possible sites to establish a small second population, but there are conflicting interests around their use, and they could do little more than hold a handful of animals. Their utilization would be better than nothing, but the ultimate solution is identifying a suitable site that can hold a viable population of over 50 animals somewhere on Java or Sumatra that can be adequately protected.

In late 2017, twelve years after I first attended that Cat Tien workshop, I was lucky enough to finally get to see a Javan rhino in the forests of Ujung Kulon. The raw emotion of seeing such a rare and magnificent animal in the wild only served to heighten my belief that this is a species that we can—and must—save. Three species of rhino have been saved and recovered through a combination of protecting them in source areas and translocating animals to new areas to establish additional populations. We have proven that we can effectively protect Javan rhinos in Indonesia, but in order to truly reduce their risk of imminent extinction these efforts need to be dramatically scaled and additional populations urgently established.

Further reading on this topic:

- Dinerstein E (2011) Family Rhinocerotidae (Rhinoceroses); in: Wilson DE and Mittermeier RA (eds) (2011) Handbook of the Mammals of the World - Volume 2: Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions

- Groves CP and Leslie Jr. DM (2011) Rhinoceros sondaicus (Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae) Mammalian Species 43: 190-208

Zoology

Zoology

Responses